He Didn’t Just Give Advice. He Invented the Whole Industry.

Before most people had ever heard the word “consultant,” there was McKinsey. Long before tech giants, billion-dollar deals, and prestigious business schools, McKinsey was already helping the largest companies make their most critical decisions. When a company needed to grow, or fix a problem, or survive a crisis, McKinsey was often the team behind the scenes. They didn’t build products or sell ads; they gave advice. Smart, trusted advice that shaped entire industries. This is the story of how one small firm didn’t just help businesses, but it changed the way they work. And in doing that, it created a whole new kind of business.

In 1926, American businesses were experiencing rapid growth. The industrial revolution had changed everything. Companies were building cars, machines, steel, and chemicals. Big factories were opening across the country. But inside those companies, something was broken.

Managers were overwhelmed. The bigger a company got, the harder it became to run. There were too many departments. Too many workers. Too much chaos. Everyone was busy, but no one really knew what was going on.

That’s where James O. McKinsey came in.

( James O’ Mckinsey )

He wasn’t a businessman in the traditional sense. He was a professor at the University of Chicago, teaching accounting. But he saw something other people didn’t. He realized that most companies didn’t actually know how to manage themselves. They didn’t have a clear plan. They didn’t know where they were wasting money. They didn’t even know which departments worked and which ones didn’t.

They needed help. Not just with numbers, but with thinking.

So McKinsey decided to leave the classroom and start something new. He opened a small office in Chicago and called it James O. McKinsey & Company. He told companies: “I’m not just here to do your accounting. I’m here to help you manage better.”

That offer was something no one else was giving at the time.

Back then, if a company had a problem, they might talk to their lawyer or their bank. But no one was trained to look at an entire company and say: “Here’s what’s working. Here’s what’s broken. Here’s how to fix it.” That kind of help didn’t exist yet. James McKinsey wanted to be the first to offer it.

He didn’t just look at the financial reports. He interviewed workers. He asked about the management structure. He looked at supply chains and sales teams and operations. Then he gave advice that was logical, practical, and based on data. It was like going to the doctor, but for your business.

At first, people were confused. They had never seen anything like this before. But soon, word spread. His clients were saving money, becoming more efficient, and growing faster. What started as a small accounting firm was turning into something entirely new.

By 1935, McKinsey had opened a second office in New York and merged with another small advisory group. He now had clients in both the Midwest and the business capital of the country. The work was growing. The demand was clear.

But then came a tragedy. In 1937, just 11 years after founding the firm, James O. McKinsey caught pneumonia and died. He was only 48.

For a moment, it seemed like the whole idea might die with him.

But in New York, one of McKinsey’s younger partners had a vision for the future. His name was Marvin Bower.

( Marvin Bower )

Bower had studied law at Harvard and also earned an MBA. He believed deeply in the mission of the firm. He didn’t just want to keep it going; he wanted to make it a profession.

He made a bold decision. He would not allow the firm to chase short-term profits. He would not let them advertise or take on easy jobs just to make money. Instead, he would build a company that puts values first, honesty, excellence, and service.

Bower wanted consultants to be like doctors or lawyers. They had to be smart, ethical, and professional. They had to speak clearly, solve real problems, and always put the client’s interest first. It wasn’t about selling something; it was about making the client better.

To protect these values, Bower took another big step. He bought out the shareholders and turned McKinsey into a private partnership. That meant the people who worked there — the partners — would also be the owners. There would be no outside investors. No pressure from the stock market. Just professionals, focused on doing the best work possible.

This structure shaped everything that came next.

Because McKinsey didn’t have to please shareholders, they could take on hard problems. They could say no to bad deals. They could focus on long-term impact instead of quick wins. And that made them different from almost every other business in the world.

The market noticed.

In the 1950s and 60s, as global trade expanded, McKinsey followed. They opened offices in Europe, then Asia, and eventually all over the world. They worked with car companies, oil companies, banks, governments, and even the United Nations. They were no longer just helping companies solve small problems. They were helping them redesign their entire business.

But here’s the secret: McKinsey never sold a product. They sold trust.

Their clients came to them with questions like:

“We’re losing market share. What should we do?”

“We’re about to merge with another company. How do we combine our teams?”

“We’re entering a new country. How should we organize our operations?”

McKinsey’s answer was never a guess. They used interviews, data, charts, frameworks, and models. They would break down a problem into small parts, test each part, and rebuild a better system. It was consulting as a science.

But because they worked quietly, and only with the most powerful companies and governments, McKinsey began to feel like a mystery to the outside world.

By the 2000s, they had more than 30,000 employees. They were advising 80% of the world’s biggest companies. They had helped companies survive recessions, enter new markets, launch products, and restructure after crises. But their name was rarely in the headlines. That was on purpose. They didn’t want fame. They wanted influence.

Of course, influence has a dark side.

In recent years, McKinsey has been criticized for working with authoritarian governments, for its role in the opioid crisis in the U.S., and for having too much power behind the scenes. People began to ask: how can one company influence so many decisions and still avoid public accountability?

McKinsey responded by promising more transparency and stricter rules. But the core model hasn’t changed. They still hire the smartest people. They still train them in structured problem-solving. They still work in teams. They still focus on client impact. And they still operate with the same core belief James McKinsey had in 1926: that good advice, based on logic and values, can change everything.

McKinsey didn’t invent computers or cars, or buildings.

But they helped hundreds of companies decide what to build — and how.

They built the playbook, not the product.

And they did it by turning advice into an art form.

That’s how one professor with a notebook and a big idea created an industry that now spans the entire world.

Final Takeaways

1. Build the container, not just the content

McKinsey didn’t just offer smart ideas. They built a repeatable system to deliver them. That’s what scaled.

2. Let silence speak

They never advertised — and that made their voice more trusted. Quiet can be powerful.

3. Standards are a strategy

McKinsey’s strict professionalism wasn’t branding. It was the business.

4. Teach people how to think

The firm didn’t scale James McKinsey. It scaled his method.

5. Trust is the real product

Clients don’t pay for slides. They pay for the process behind them — and the years of credibility that earned it.

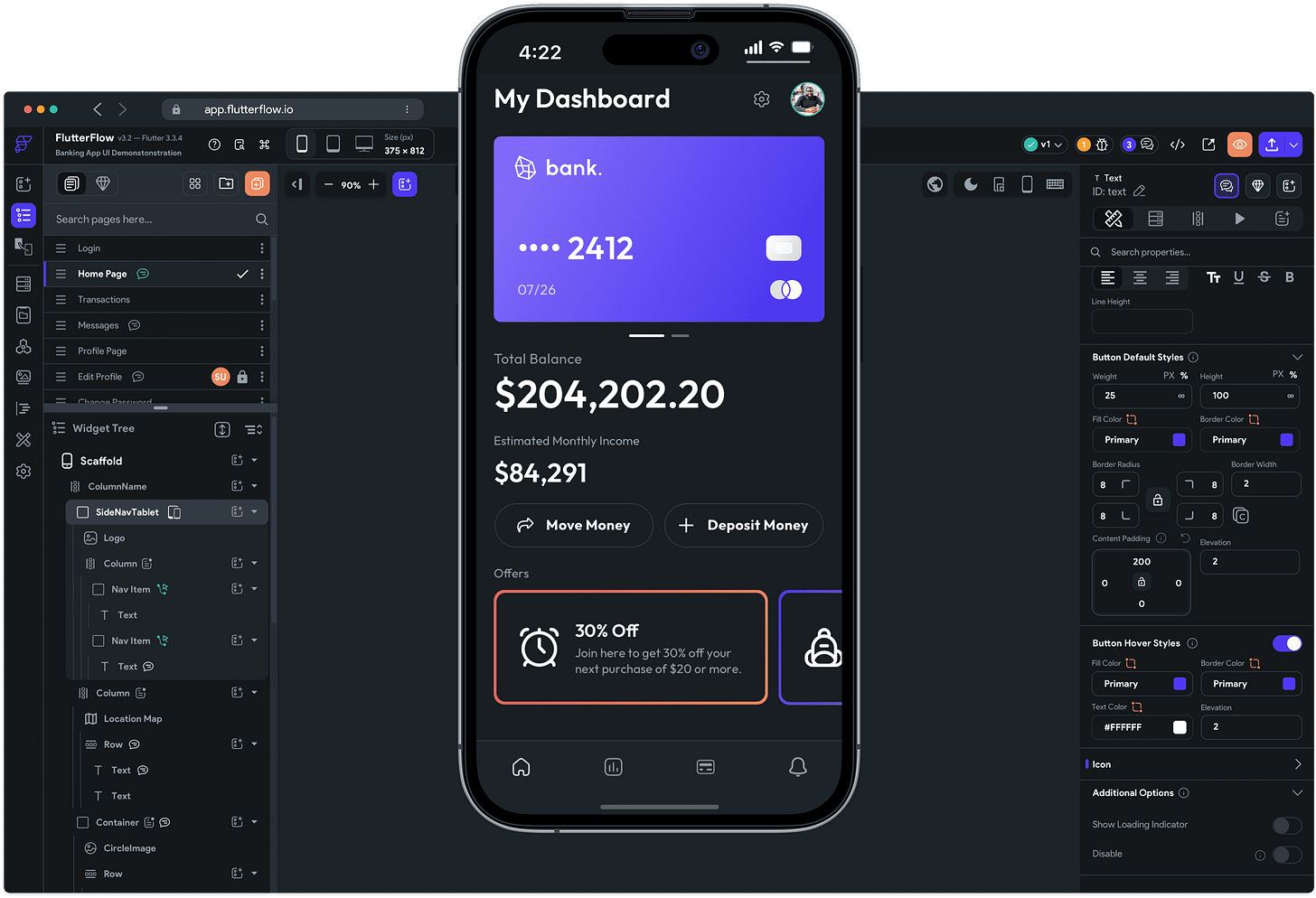

AI tool of the week.

Flutterflow lets you build full web and mobile apps without writing code, perfect for founders and teams who want to move fast from idea to launch.